Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia (1999) is often described as a sprawling ensemble drama, it weaves together multiple storylines over a single, rain-soaked day. On the surface, it’s a mosaic of human experiences, with betrayal, grief, regret, and fleeting hope.

I enjoy a good wallow in the pit of despair at the cost of a characters psyche. Magnolia hits that button square on. It has heart, humor and emotional turmoil all rolled in to a full on three hours. Another couple that are good for this on one end of the scale is The Savages (2007) and on the other end of the scale, Tyranosaur (2011)

But dig deeper, and you realize that Magnolia is more than a story about dysfunctional families or chance encounters; it is a mirror of personal horror, the subtle terror of confronting the darkness within ourselves. It is one of my favorite guilty pleasure movies, reveling in the catharsis of other people’s pain knowing your turmoil could be a whole lot worse. If you have ever been in the depths of despair, you can relate that it is very hard to see the top of that hole you find yourself in.

The Ordinary as a Source of Horror

Let’s get this straight, Magnolia is not a horror. It is a day in the life drama. Instead, the film finds terror in the ordinary: a failed relationship, a parent who abandons, a childhood scar that never heals. Each character in the movie faces the horror of their own choices, the crushing weight of guilt, or the fear of inevitability.

Taking place in the lives of eight main characters and covering a range of emotional and physical trauma. These arcs weave together, ebbing and flowing in a traumatic and emotional kaleidoscope. Finally building to a collective emotional crescendo rather than a single climax or resolution. The use of different perspectives and interwoven story lines emphasize the way trauma can flow though generations without being resolved. The events affecting more than the direct people involved. Think the interconnected stories of Pulp Fiction and even in the character segments in Weapons (2025)

Take two titular characters:

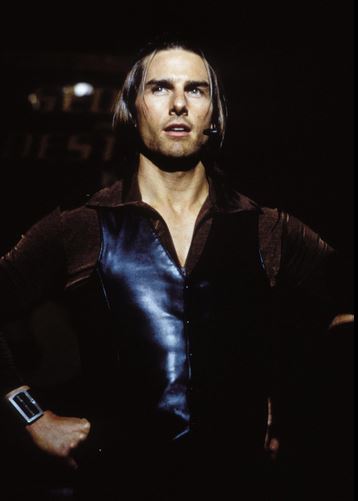

Frank T.J. Mackey, the self-help guru (played delightfully by Tom Cruise), embodies a terrifying mix of bravado and vulnerability. His obsession with control masks the terror of emotional intimacy. The horror here is existential: the fear of being powerless in the face of one’s emotions. After the bravado of the majority of the film, Frank gets his final moments with his father.

Claudia Wilson Gator struggles with addiction and parental neglect and more, haunted not by a ghost, but by a lifetime of emotional trauma. Her horror is deeply personal, rooted in memory and shame. The light at the end of the tunnel shows a small glimmer for Claudia after meeting Jim.

This non linear approach resonates with because it reflects real life: often, the scariest monsters are ourselves. We often get so entrenched in where we have found ourselves that we continue as we are even though when we really look at ourselves, we are the harm that we feared and tried to get away from.

Man, this movie sounds like a real downer, who would want to watch it? Well, it is a vast and sprawling movie, weaving in and out of the characters lives. For the most part you can feel that they have made their own beds by not taking control of their lives. But that is being human, we are flawed, we have problems – some beyond our control. But the movie (although you could say, over dramatically) makes us confront the trauma of not sorting out our feelings or actions.

Use of Chance, Coincidence, and Cosmic Horror

The film’s iconic raining frogs scene feels absurd, almost supernatural, but it amplifies the theme of unpredictable chaos in life. This is the horror of realization: sometimes, events spiral beyond our control, there is not logic, sometimes things just happen beyond out control. The universe’s indifference is unsettling, Magnolia captures this fear that life is arbitrary, and suffering can descend like a sudden, inexplicable storm.

Interconnected Pain

Magnolia also highlights on the horror of interconnection. Characters’ lives intersect in ways they can’t anticipate or control. The film suggests that personal horror isn’t isolated, it spreads, touching those around us.

Jimmy Gator, a game show host, must face the consequences of decades of emotional neglect. Can a lifetime of hurt that you have given others be redeemed before it is too late?

Donnie Smith, the timid man, experiences humiliation that seems small but is deeply scarring for him. Can we see the foreshadowing in young Stanley’s life, could he become Donnie in the future?

We can recognize these threads in our own lives. The horror isn’t just external—it’s the way our mistakes, secrets, and regrets ripple through relationships, shaping both our world and the lives of others.

The Mirror of Personal Horror

At its core, Magnolia forces us to confront what it means to suffer alone yet be part of a larger human tapestry. Unlike a standard horror movie, the terror isn’t in the chase or the scream—it’s in the recognition:

“This could be me. This is me.”

When we watch Frank, Claudia, or Donnie, we see our own failings, fears, and unresolved grief reflected. And that reflection, unflinching and unapologetic, is profoundly unsettling. The horror is intimate, psychological, and sometimes spiritual. They never seem to find redemption, forever pulled down by their internal torment.

Magnolia as Horror beyond the monsters

Magnolia reminds us that personal horror doesn’t need monsters or gore. It exists in emotional vulnerability, the fear of regret, and the chaos of human connection. It is in the realization that we may be powerless to change certain outcomes, yet we continue to search for meaning, redemption, or forgiveness. Think about your favorite horror movie, the personal elements pull the characters along, they are vulnerable, out of their depth.

In the end, the horror is human—and perhaps, through that recognition, a glimmer of hope can emerge for us. As terrifying as it is to face ourselves, Anderson’s Magnolia suggests that confronting the horror within is the first step toward truly living our lives.

Leave a comment